Insights from a Predictive Model Pipeline Abstraction

This post was originally published on Medium

When building a complex system, it’s often helpful to think about the design of that system using patterns and abstractions. Architects and software engineers do so frequently, and the experience of implementing predictive modeling pipelines has recently led to a variety of patterns and best practices. For instance, when dealing with large amounts of streaming data, some organizations use the Lambda Architecture to handle both real-time and computationally-intensive use-cases.

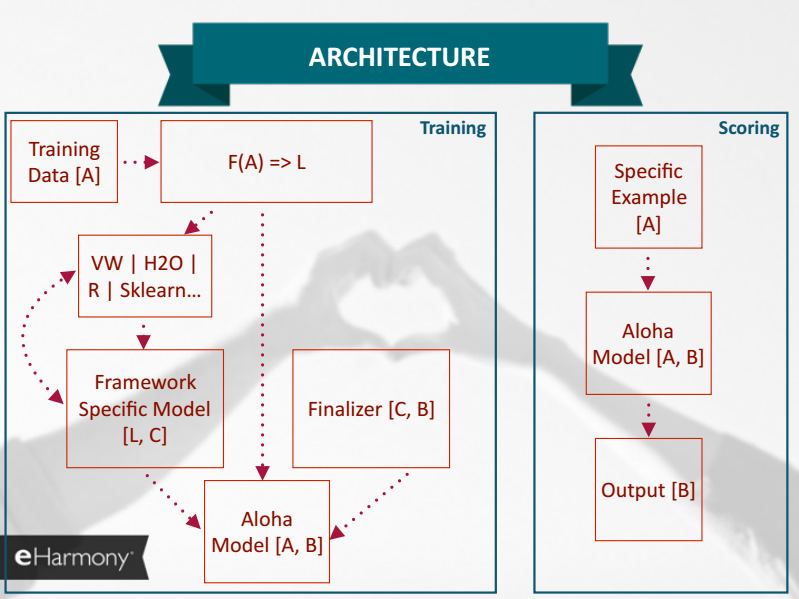

I recently attended the Strata conference here in NYC, where one of the better presentations was by Jon Morra, at the time at eHarmony — A Generalized Framework for Personalization. He discussed a number of interesting topics, but I’d like to focus on his use of a representation-focused abstraction for the components of a predictive model.

One of Jon’s slides looks like this: Model[A, B] =: f(A) => B. This bit of formalism defines a predictive model as a function with two type parameters, A and B, where A is the type, or representation, of the input, and B is the output of the model. This is sort of obvious, but Jon then puts this into a broader context, which is where the insight arises.

from Jon Morra

from Jon Morra

For a predictive model to be well-integrated with consuming applications and other supporting tools, it’s critical that the representations that are used to communicate between systems are well-defined and consistent. Specifically, the application will represent an entity to be scored, provide that to the predictive model, and expected back a score. In a Service Oriented Architecture, this is the Standard Service Contract principle — define a data schema to be used consistently between services. Critically, the entity to be scored is represented using the structures and semantics of the application domain, not the model’s internal domain. I’ll refer to the type, or representation, of this entity as DomainEntity.

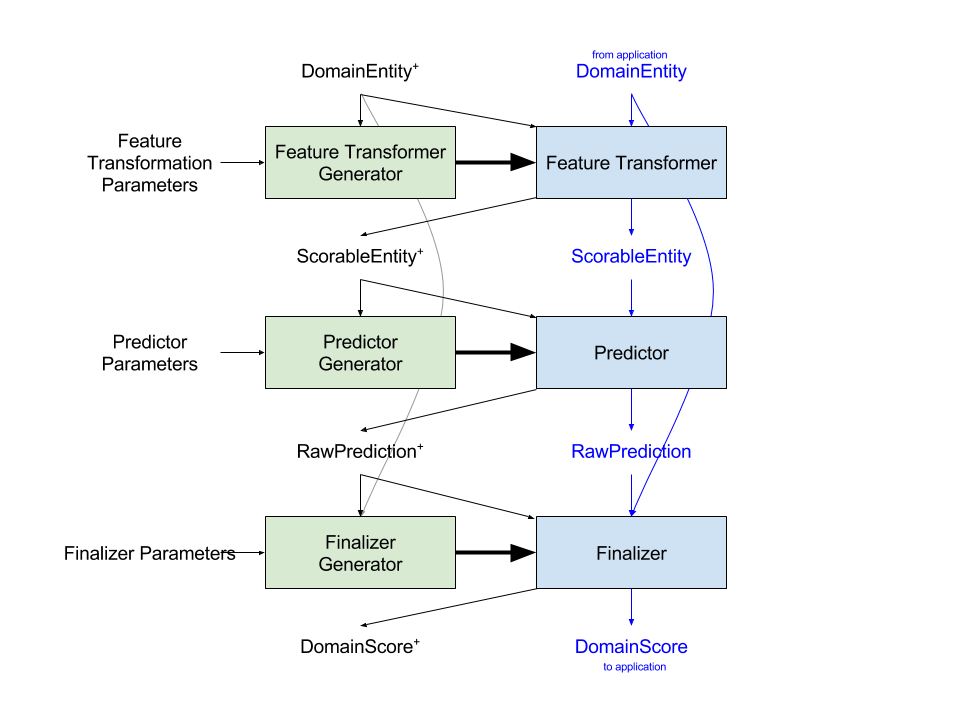

Beyond this relatively basic insight is the idea that there are two other important types. To explain in more detail, I’ve expanded and clarified Jon’s diagram using CamelCase variable names instead of letters. (As a programmer, single-letter variable names are anathema! I don’t know why mathematicians insist on using them so extensively.)

There are two processes, with shared representations and some shared processes. First (black) is the Training process. Each (green) step in Training is a functional — a system that takes a set of data and a set of parameters, and generates a new function (blue). Together, the generated functions define a pipeline for Scoring, and each Training step has an analogous step in the Scoring process.

The first step is Feature Transformation — the process of converting from a DomainEntity representation to a ScorableEntity representation. Critically, this step happens inside the model — a change to how features are generated or how the core learner works should (must!) require no change to how the application provides an entity to the system. Your DomainEntity could be text, or a hierarchical structure, or something else, but your ScorableEntity is likely some sort of vector of numbers.

Worth noting is the insight that, according to this abstraction, the DomainEntity objects that are used for training and scoring must be the same. To implement this in practice means either having two pieces of code (one in training, one in the application) that do essentially the same thing, or that there should be a shared service that provides DomainEntity objects (either historical or current) upon request.

The second step is Prediction. The process of executing the Predictor Generator to create a Predictor is usually called “learning.” The input to learning is a set of parameters and a set of ScorableEntities, and the output is a Predictor that can generate a RawPrediction, given a ScorableEntity. This is the core of the model, although architecturally it’s just a subset of the overall system. Ideally, the Predictor Generator is off-the-shelf or a minimally-wrapped version of a standard learning algorithm.

The third step is Finalizing — a transformation from the RawPrediction to some sort of DomainScore. Frequently, the output of the Predictor is not appropriate for display to an end-user, but must be transformed in some way. This could be normalization, or ranking, or combination with the outputs of other systems. For example, at a previous job, the (basic) RawPrediction we were generating was a likelihood that a college student would graduate. But this underlying probability score was binned into institution-specific red/yellow/green categories for display, based on how that specific institution wanted to think about and talk about risk.

Note in the diagram that the Finalizer has access to the raw DomainEntity properties, but not to the ScorableEntity features. The Finalizer is implementing business logic, not predictive modeling, so it should process data at the domain level. The abstraction suggests that Finalizing should be thought of, and architected as, a separate module, or perhaps even a separate microservice.

It may be that thinking about a predictive system in these terms could help you make better decisions around system architecture and representations. Of course, abstractions are just that — a way of organizing thinking. This may not be the best-possible abstraction. And even if it was, real-world concerns would mean you wouldn’t necessarily implement an abstraction exactly as written. And you shouldn’t re-architect a system just for the sake of elegance, if it’s working and not causing problems. Still, being aware of what good patterns look like and what a good direction to move in is critically important when evolving and growing a complex system over time.