Patterns for Connecting Predictive Models to Software Products

This post was originally published on Medium

You’re a data scientist, and you’ve got a predictive model — great work! Now what? In many cases, you need to hook it up to some sort of large, complex software product so that users can get access to the predictions. Think of LinkedIn’s People You May Know, which mines your professional graph for unconnected connections, or Hopper’s flight price predictions. Those started out as prototypes on someone’s laptop, and are now running at scale, with many millions of users.

Even if you’re building an internal tool to make a business run better, if you didn’t build the whole app, you’ve got to get the scoring/prediction (as distinct from the fitting/estimation) part of the model connected to a system someone else wrote. In this blog post, I’m going to summarize two methods for doing this that I think are particularly good practices — database mediation and web services.

There are a few reasons why this matters. First of all, it’s highly unlikely that the world you care about is static. You’re going to have to refit and re-integrate your models, likely pretty frequently. If iteration is painful, it’s not going to happen, and the model’s value will stagnate. Fast, easy iteration is critical. Secondly, the system you’re integrating with probably isn’t static either. If it changes, will your model stop working? (Or worse, start predicting garbage?) A resilient architecture is also critical.

Overall, you need what software architects call “separation of concerns.” You don’t need to know the font your prediction is rendered in, or even if it’s text or a graphical widget. And the app needs to know how to request a credit score/flight price/list of people you may know. But it doesn’t need to know how you’re computing that. Most importantly, it really (really) doesn’t need to know how you’re doing feature engineering. The interface must happen before you transform the raw entity data into whatever format goes into the mode.

On a deeper level, Conway’s Law, an insight from the 1960s, is highly relevant: > Organizations which design systems … are constrained to produce designs which are copies of the communication structures of these organizations.

This means that if your application Software Engineers are separate from your Data Scientists, and they likely are/probably should be, then your software will have an interface that reflects the handoff between those two teams. So you owe it to yourself and your colleagues to design that interface in a way that enables fast iteration, resiliency, and a good separation of concerns.

Option A — use a database. If the entities (people, flights, whatever) you need predict don’t change very often, and in particular, they don’t change or suddenly appear right before you need to make a prediction, then I recommend you consider a good old-fashioned database. The application is probably storing everything in a nice, clean, normalized set of tables. In many cases, using those tables is the simplest and best option.

A good approach that I’ve used in production is to use an equally-venerable technology: batch jobs. Every hour or every day, have a script run that pulls entities from the application database — maybe just the ones that have changed recently — transforms them into the format needed for prediction, runs the prediction method, then writes the results back to the database.

The advantages of this are substantial. You can update your model, or even totally replace it, as long as it writes to the same prediction tables the same way. No need to coordinate with the application’s release cycle in most cases. Tools for reading and writing databases are mature in any language you’re likely to be writing a model in.

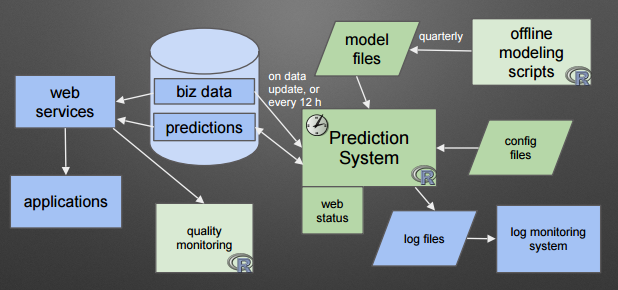

A database-mediated architecture diagram I designed and implemented a while back.

A database-mediated architecture diagram I designed and implemented a while back.

There are complexities, of course. You need monitoring. If some input causes your model to crash before it writes predictions, you don’t want to learn about it weeks later. So use good error-logging practices and set up a log-monitor that will alert people in case of a problem. You should be evaluating the results, both from a statistical point of view (an accuracy measure) as well as a utilization point of view (are people using the feature and do they come back?). As Ruslan Belkin from LinkedIn says: > There’s only one right answer and starting point for a data product: Understanding how will you evaluate performance, and building evaluation tools.

Another complexity is that if you’re reading from the application database, you’ve potentially created a problem where the application developers’ upgrading the database schema can break your model. Be very careful, use good database schema migration practices and testing, and consider creating a separate database schema, owned by the data science team but populated by the application, just for model fitting and scoring.

Option B — web services. Great, you say, but my model needs to make a prediction for a person who just connected their Facebook account 30 seconds ago, so a batch job isn’t going to cut it. In that case, use the standard pattern of complex software systems these days, a web service. Leveraging some of the technology of the web (HTTP), along with some standard patterns (REST), service-oriented architectures/microservicesassume that each development team is creating a standalone subsystem that talks to other subsystems over a network connection.

What’s needed to make this happen? First, the application can no longer be passive. It has to create a description of an entity to be predicted that your model can consume. Most likely, this description should be JSON or XML, and the syntax and semantics must be clearly documented. How do you represent time? Should the application send a null if information is missing, or a 0? You know the answer is a null, but those programmers will probably send you a 0 if you don’t clarify.

Second, your application should apply the same feature engineering during real-time scoring as it did during model fitting. This is a tricky problem. When creating the model, you probably loaded data from relational databases or Hadoop and created something like a data frame or matrix. But if you’re scoring with a web service, you don’t have a database, just a JSON object, so your feature engineering logic won’t work.

The student success (likelihood of graduation) model that my team and I at EAB built avoids this problem by converting database tables to a JSON-equivalent object during model fitting, even though it’s not technically necessary. But by doing so, we can use literally the same code to build the model matrix used for scoring as we did for fitting, which reduces the likelihood of hard-to-detect scoring bugs.

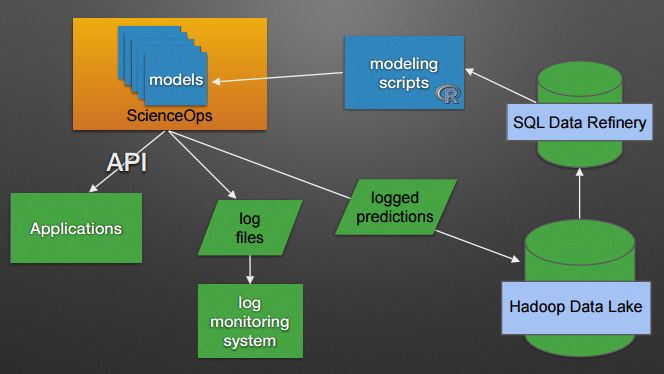

Architecture of EAB’s Student Success model, roughly.

Architecture of EAB’s Student Success model, roughly.

Third, your application is now part of a real-time user experience. Congratulations! Now you get to think about DevOps, reliability, and response times, as if you were a computer scientist! There are a couple of options here. If you’re writing in Python, it’s not that hard to write a simple Flask web app that accepts a JSON object, predicts with it, and returns the result. Of course, the real world can make that an inadequate solution. What if you have lots of services, not just one? What if your server needs to go down for maintenance, or gets overloaded?

There are several commercial tools available to make this easier. I’ve had good experiences with YHat’s ScienceOps, which supports a cluster of individual R or Python models wrapped in Docker containers for safety. Domino Data Lab has a similar system, as does Microsoft(via their purchase of Revolution).

So, I’ve presented two good patterns, neither of which are what you might call simple. If these are good patterns, what are less-good patterns?

A common one that doesn’t give you the ability to iterate rapidly is to throw a model over the wall, and ask Software Engineers to re-implement it in C# or Ruby or even in SQL. This might be possible for a simple linear model, but if you find later you can get much better results with a Deep Learning model, now you’re going to have to get the development team to refactor their entire architecture, which is going to take months, best case. Don’t throw models over the wall — it violates Conway’s Law and will definitely hurt you long-term.

A seemingly promising approach is to extract the coefficients or structure of the model into a standard format and provide them to a system that knows how to predict using that format. The PMML (Predictive Model Markup Language, an XML standard) attempts to do this. But it has a generally-fatal flaw in that it doesn’t support much feature engineering. If your entities have any sort of hierarchical or temporal or spatial structure, you’ll have to put the feature engineering on the wrong side of the interface, beforeU the PMML scorer, inside the core application. And now if you ever need to change anything, you have to get in line behind everyone else with a feature request. Bad news for you. There’s a new descendant of PMML that attempts to address this issue — PFA (Portable Format for Analytics) supports pre-processing and post-processing. It will be interesting to see if it takes off.

Another anti-pattern is to embed a model written in one language inside an application written in another, using a tool like RinRuby to pass data back and forth. Seems like a good idea at the time, but now your deployment environment has to support two environments, with all the dependencies and libraries that may be required. Testing for new deployments becomes a lot harder, too, and you’re tied to the application developer’s deployment cycle, which will make you much less flexible.

Overall, I think you’re best off trying to design a database-mediated or web-service based approach. There may be exceptions and good alternatives, especially if you’re in a Big Data environment, or if your data product needs to be rendered as a complex graph. But for the traditional medium-data predictive model, with a substantial systems development lifecycle, focusing on making the application/model interface as clear as possible is your best bet.

Like what you read? Find the intersection between software engineering and data science compelling? EAB is hiring! As of when this article was posted, we have open roles in Engineering-focused (type B) data scientists, at both more junior and more senior levels. Help us build systems used by students and staff at about 200 colleges and universities!